There's no escaping human connection

In The Great Divorce C. S. Lewis describes hell as an endlessly expanding, empty city. The people who live there are forever trying to get further away from each other, moving further outwards in an effort to find a comfortable isolation. It's a place where you can have anything you want just by imagining it, but nothing is really real. The houses are beautiful but the rain falls right through them.

Anyone can leave hell whenever they want. A bus comes every day that will take you away to a clearing where you'll be met by someone you knew when you were alive. They'll walk with you to heaven, but the journey will hurt. Because you've been living in hell so you are now no longer quite real and everything around you is. The grass stabs at your feet, the water is as hard as stone.

And more than this, your guide will ask you to talk about who you actually are. They'll ask you to confront and consider the life you lived, to see yourself clearly and honestly and accept what you see.

None of us like being honest about who we really are, even with ourselves, but the idea of doing that with another person is excruciating. Of all the things we know we must do in order to be fulfilled and healthy human adults, being vulnerable with other people is the worst.

We like to delude ourselves, I think, into believing that all our frailties are insignificant as long as no one knows about them. What does it matter that I'm petty, or lazy, or broken if no one else is ever aware of that I am?

Of course, the more we are hiding, or believe ourselves to be hiding, the harder it becomes to feel connected to other people.

It's very easy to hide, in the modern world. As it has become easier to engage with our friends online, it's started to feel less essential to see them in person.

All of which has coincided with successive economic crises that have left more of us living in various states of financial precarity – exploited by a labour market that knows we're desperate, managing side hustles on top of jobs, awash with guilt for every moment we spend unproductively.

It can manifest even in moments that should be connective. We might find ourselves feeling not fully present; parts of our minds forever focuses on the stress of trying to survive in a world that seems to increasingly want us to fail.

A couple of years ago I had a freelance gig that involved watching a lot of the show Catfish and what stood out to me is how often the messages sent by the catfish were completely generic. The hosts would ask that episode's guest what it was that had made them fall in love and they'd talk about how whoever was on the other end of that conversation made them feel special. But they were doing that simply by saying you're so special. There was never any indication that they liked or had even noticed anything individual and specific about that person.

It's the same kind of thing you see in all the people developing deep attachments to LLMs. Chat GPT can create a good enough facsimile of someone who is paying attention to you to satisfy a person who feels neglected in their actual life. And it's so easy to feel neglected these days.

It becomes this self-perpetuating cycle. We're under strain and when you're under strain maintaining even those relationships we most cherish can start to feel like an obligation, let alone engaging with strangers. How lucky, then, that so much human engagement is now unnecessary.

You can use the self-checkout at the supermarket. You can update your phone contract online, instead of calling and speaking to someone. We've been sold this as a good thing, and honestly for the longest time I've believed it. It's more efficient to do this, depending on how efficient you are as a person, it leaves you more time for things you'd rather be doing.

Aren't we all happier in this efficient, lonely world? This seamless modern technological miracle of a world where we don't have to chitchat with the person scanning and bagging our groceries?

What technology has done for us, I'm starting to think, is to experience the world a little bit more like the rich do. The rich have never had to interact with anyone they don't want to. They've had servants to do that for them, servants they can also choose to barely acknowledge. And why should you have to interact with people whose lives are so thoroughly unconnected from your own.

The thing is. The thing I think about more and more these days, is: their lives are, in fact, inextricably intertwined with yours. It's the inescapable truth of human existence.

Your life is connected to everyone else's life – to Elon Musk's, to Taylor Swift's, to the transport workers you barely notice on your commute to work, to the homeless person begging on a street you've never once walked down.

The rich were fools to attempt to deny this for all these years, and we are fools for letting technology make us complicit in this denial.

I don't meant this in a crunchy, we are all one kind of way. I mean it as a solid fact. The chains between us might be long, but the links are steel. We used to be able to see them more clearly.

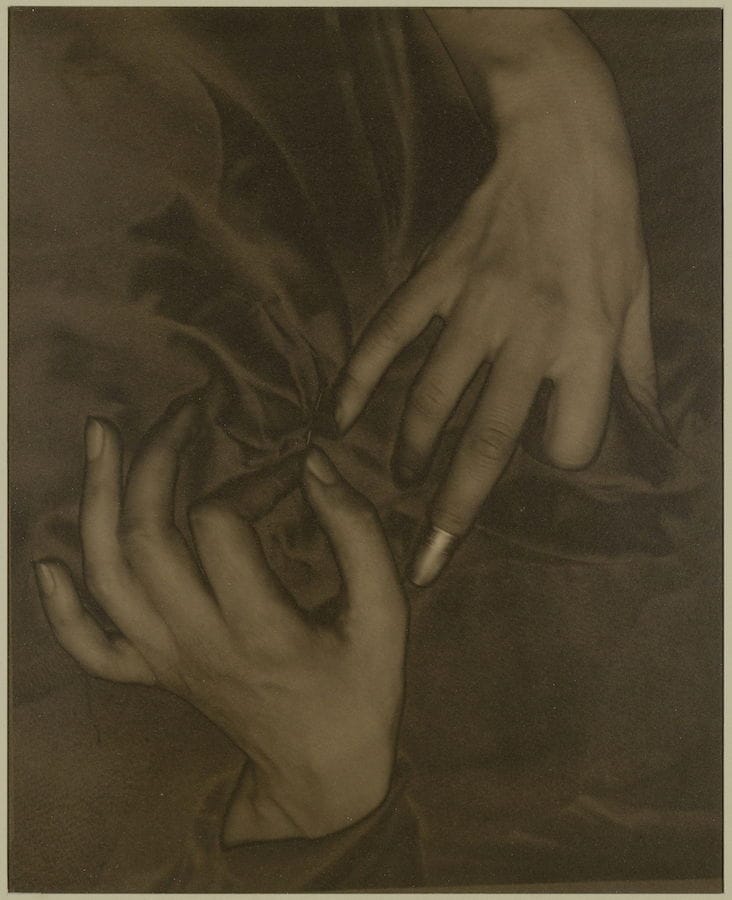

A globalised economy allows us to dismiss a huge amount of the people whose hands are on our lives. We know this, really. We know our clothes were sewed by people, for example, in factories. If we can afford it and trust an ethically sourced label when we see one, people who were fairly paid and treated well. But we know, also, there's a high likelihood we're wearning something that was made by someone on poverty wages working fourteen hour shifts.

This knowledge also pushes us to the belief in our own isolation. We feel powerless to prevent the evils of the fashion industry, we're not sure how to escape our complicity in it. There is no ethical consumption under capitalism and all.

I think there's value in trying to remember though, not so you can save the sweatshop workers (we can, we one day hopefully will, but not immediately, not on our own) but so you can remember the links between you and the wider world.

Your clothes were sewed by people who's inner lives are as rich and intricate as your own. The person who attached the eyelets on your sneakers went home and smelled their baby's head. They watched a movie that made them cry, they saw a sunset that struck them through the marrow with wonder at its beauty.

We think of things you know, of items as being either factory produced or handmade, but everything is handmade. A potter can be an artisan or a hobbyist they can be someone on a factory assembly line sticking identical handles on straight sided mugs that will be glazed white and printed with world's best mum and picked up in a rush by someone who's wife is reentering the workforce after having children.

All of which is important not just so we have a wider sense of our identity as part of a vast collective, but so we are better able to conceptualise our actions as impacting others.

If someone is too quick sticking one handle on one mug, someone else ends up with coffee and broken china all over the floor.

The efforts of the rich to separate themselves from others don't get them their own distinct world, just the illusion of them. They know this. That's why they pour more and more money into maintaining that illusion.

Private islands, secure estates, hiring the whole of Venice for a wedding – all ways of avoiding other people, normal people, people's whose poverty is created by their wealth.

Extreme wealth disparity puts the rich in eternal fear of those who want what they have and so they spend their money keeping them at a distance. The more wealth they have, the more poverty they've created, the more distance they need.

Physical distance, social distance and, if necessary, legal distance. Much of the criminal justice system is concerned with protecting property, which makes sense when you remember that the vast majority of property is held by a very small amount of people who wield incredible power over how the rest of society is structured.

And while the rest of us might openly chafe against some symptoms of their control – obvious political corruption, exploited workforces, sky rocketing housing costs and the like – we're less inclined to talk about their impact on incarceration. It's difficult. It's grimy and weird and we don't like to touch it. After all, there are plenty of people that we also want to be kept safe from, and isn't that what prisons are for?

I suspect that what most people want from the criminal justice system is to not have to think about criminals. To consign them mentally to somewhere else so that we can go about our days assuming we're safe from them. But criminals are still here on this planet, impacting and being impacted by other people, who go on to impact more people, until that chain of impact reaches you.

I don't know that I have a pithy conclusion to this. I don't know that I have a clear point. I just think it's possible that an important counter to all of this, you know, to the way of things right now, is becoming better at acknowledging each other as people. We talk about building community as if it's this grand thing, the rank and file taking to the streets as one, do you hear the people sing.

But it starts small. It starts with recognising that there is another person on the end of every single thing we interact with. It starts with acknowledging how deeply we are impoverishing ourselves as we forget them.